AUCTORES

Globalize your Research

Review Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.31579/2643-6612/025

1 Department of periodontology and oral implantology, M a rangoonwala college of dental sciences and research centre, pune.

2 Associate professor Department of periodontology and oral implantology.

3 Prof and head of departmentDepartment of periodontology and oral implantology, M a rangoonwala college of dental sciences and research centre, pune.

*Corresponding Author: Sharayu R Dhande, Department of periodontology and oral implantology, M a rangoonwala college of dental sciences and research centre, Pune, India.

Citation: Sharayu R Dhande, R Hedge, S Muglikar. (2022). Main Title: Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans : Current Overview. Dentistry and Oral Maxillofacial Surgery. 5(1); DOI: 10.31579/2643-6612/025

Copyright: © 2022 Sharayu Rajendra Dhande, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: 13 October 2021 | Accepted: 28 November 2021 | Published: 04 January 2022

Keywords: actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans; aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans; virulence factors; leukotoxin; aggressive periodontitis

Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans is one of the most aggressive pathobionts studied to the date. It encodes numerous putative toxins, the complex interplay of these toxins with the subgingival microbiota affects host defense mechanisms leading to rigorous destruction of the periodontium further causing loss of the tooth. The diversity in the field of oral microbiology has renewed interest among clinicians to study the bacterial species in particular. The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive update on this commensal bacterium and co-relation of its virulence factors with the periodontal disease.

The expanding field of Oral microbiology with a focus on periodontal diseases, particularly the localized form of aggressive periodontitis caused a renewed interest in the bacterial flora. Bacteria were first observed by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1676, using a single-lens microscope. He called them "animalcules" & published his observations in a series of letters to the Royal Society. The name bacterium was introduced much later, by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg in 1838. Louis Pasteur demonstrated in 1859 that the fermentation process is caused by the growth of micro-organisms, & that this growth is not due to spontaneous generation. Later, Robert Koch, Pasteur advocated the germ theory of disease and was awarded a Nobel Prize for the same in 1905 [1].

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A.a) is one of the most virulent periodontopathogen studied till date. It is a fastidious, facultatively anaerobic, nonmotile, nonhemolytic, non-sporing, small gram-negative rod [2]. It is also a prominent member of the HACEK group that comprises of (Haemophilus species, A.a, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella kingae) of pathogens [3].

Beginning in the late 1920s a series of Oral & Medical Microbiologists believed that periodontal disease was a result of mixed infections. This hypothesis has been considered from the late 1800s. 1880 to 1930 is widely known as “Golden Age of Microbiology”. Scientists identified 4 different groups of potential etiologic agents (amoeba, spirochetes, fusiforms & streptococci) for various periodontal diseases using different techniques. Researchers suggested specific plaque hypothesis based on these findings [4].

However, with advancements in bacterial identification techniques, many other bacterial species were identified in dental plaque derived from periodontitis patients. Studies conducted between 1930 to 1970 failed to identify any specific micro-organism as the etiologic agent of periodontal diseases which led to the proposal of non-specific plaque hypothesis, according to which increase in plaque mass is essential for causing periodontal tissue destruction [5].

Later on, as the research progressed in the field of microbiology, immunology & molecular biology numerous studies concluded a putative pathogenic role of numerous bacteria, including mainly Gram negative. These include A.a, Tannerella forsythia, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella Intermedia, Campylobacter rectus, Treponema denticola, Fusobacterium nucleatum. Virulence factors produced by these micro-organisms have been identified & their role in periodontal tissue destruction is well established. These findings led to the Return of the theory of Specificity in the microbial etiology of periodontal diseases. Presently, the concept of “polymicrobial dysbiosis” is been investigated to explain the role of specific micro-organisms in causing periodontal destruction.

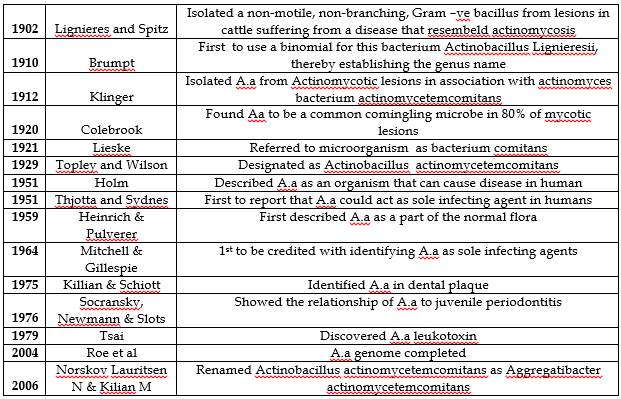

History: [1,6-18]

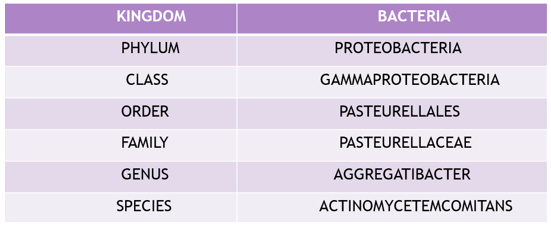

Bacterial Taxonomy: A.a is a member of the genus Actinobacillus that belongs to the family Pasterellaceae. This family was constructed to accommodate a large group of Gram –ve, chemo-organotrophic, facultative anaerobic and fermentative bacteria consisting of genera- Pasteurella, Actinobacillus and Hemophilus. Most members of this family cause disease in mammals including humans, birds &/or reptiles. The name Pasterellaceae was proposed for the family according to the oldest recognized genus of the group, Pasteurella.

The Journey from Actinobacillus to Actinomycetemcomitans: [19-21]

The genus name Actinobacillus refers: actin : star shaped, bacillus: rod shaped

Actinomycetum comitans- with actinomyces referring its close association with Actinomyces israeli in actinomycotic lesions.

Bacterium actinomycetemcomitans was co-isolated with Actinomyces from Actinomycotic lesions about 100 years ago.

In 1929 it was classified as Actinobacillus Actinomycetemcomitans, despite limited similarity with Actinobacillus Lignieresii.

In 1962 phenotypic resemblance of Actinobacillus Actinomycetemcomitans was noted with Haemophilus aphrophilus and hence, a subsequent relocation to genus haemophilus.

Finally in 2006 new genus Aggregatibacter was created to accommodate Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans (A.a), Aggregatibacter aphrophilus, Aggregatibacter Segnis and Aggregatibacter killiani.

Norskov Lauritsen N & Kilian M in 2006 changed the name to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans due the phylogenetic similarity between A.a, Hemophilus aphrophillus, Hemophilis paraphrophilus. Therefore, all these were grouped under new family Aggregatibacter.

Morphological, Biochemical and Growth Characteristics:

Morphology: A.a is Gram –ve, coccobacillus approximately about 0.4 ± 0.1 × 0.1 ± 0.4mm in size (Zambon 1985). Upon primary isolation, A.a forms small colonies approx, 0.5mm – 1.0mm (Slots 1982) in diameter. A.a is capnophilic requiring an atmosphere containing 5-10% CO2 for good growth. It is microaerophilic, a facultative anaerobe and can grow under anaerobic conditions. A.a is non-sporulating, non-motile, non-hemolytic, oxidase and catalase +ve. The fermentative ability of A.a strains to utilize galactose, dextran, maltose, mannitol & xylose permits the bio-typing of this organism into several bio-types & serves to distinguish this organism from other members of the oral flora. Upon primary isolation A.a forms small colonies approx. 0.5-1.0mm in diameter but does not grow on Mac Conkey’s Agar. The colonies are translucent (or transparent) with irregular edges appear smooth, circular & convex. The colonial morphology of fresh isolates is distinctive with star shaped morphology form in the agar that gives A.a its name. In addition to having a star shaped internal structure, colonies of fresh isolates are rough surfaced. Repeated subculture yields, two types of colonial variants: one is smooth-surfaced and transparent, smooth-surfaced and opaque. The transparent smooth-surfaced variants appear to be an intermediate between the transparent rough-surfaced & opaque smooth-surfaced types. (Inornye et al 1990). The colonial variation is associated with fimbriae [2].

Surface Ultrastructure of A.a : Includes Fimbriae, vesicles and extracellular amorphous material.

Fimbriae: Fimbriae are small filamentous cell surface appendages associated with bacterial colonization of host tissues. Fimbriae in A.a & may be peritrichous arrays of more than 2µm in length and 5nm in diameter & often occur in bundles (Ofek 1980). Fimbriated strains produce colonies with a star-shaped interior structure- designated star +ve, strains that lack a structured interior are designated star –ve. Fimbriated variants exhibited levels of attachment up to 4 fold greater than their non-fimbriated variant (Rosan et al 1988). Non-fimbriated A.a also exhibit adhesive properties indicating that non-fimbrial components also function in adhesion (Meyer-Fives Taylor et al 1994) [22].

Vesicles (Blebs): Electron Microscope has demonstrated membrane vesicles (blebs) that appear to be released from the cells. Vesicles are prominent feature & present in large numbers on the surface of A.a. These vesicles are lipopolysaccharides in nature. Vesicles exhibit adhesive properties. Vesicles exhibit leukotoxic activity (Hammond et al, 1981). Vesicles also contain endotoxin, bone resorption factors & a bacteriocin called Actinobacillin. (Hammond et al, 1987). Vesicles function as delivery vehicles for A.a toxic materials (Meyer et al, 1993).

Extracellular Amorphous Materials: Surface of A.a cells is associated with an amorphous material that embeds adjacent cells in a matrix (Socransky 1980). Expression of amorphous material is determined by culture conditions. The material is a protein most likely a glycoprotein & has been shown to exhibit both bone- resorbing activity & adhesive properties. Bacteria from which the amorphous material has been removed exhibit reduced adhesion to epithelial cells (Holt & Socransky 1980). Conveyed adhesion increases levels of adhesion when suspended in extracellular amorphous material.

Biochemical Properties of A.a : Slots in 1982 studied 135 biochemical characters in 6 reference strains and 130 strains of A.a freshly isolated from the oral cavity. All isolates were small motile capnophilic G-ve rods that did not require factor X(Hemin) or factor V (NAD) grows in the absence of serum/ blood. A.a is capnophilic, requiring an atmosphere containing 5-10% CO2 for good growth. It is microaerophilic & a facultative anaerobe & can grow under anaerobic conditions [23].

Culture Medium: Malachite Green Broth (MGB) with malachite green and bacitracin was the earliest media used to culture (A.a). Exclusive growth of A.a was found in a particular culture medium which contained TSBV (Trypticase soy agar and serum with bacitracin and vancomycin – it is an excellent primary selective medium for A.a that detects micro-organisms in levels as low as 20 viable cells per ml – Slots J 1982), spiramycin, fusidic acid and carbenicillin. Colonies identified on basis of adherent colonies and positive catalase reactions. Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) – 1640 and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium are used now with a generation time of 246 and 346 min [24].

Effect of Supplements: [23, 24]

Yeast extract – addition of increasing amounts of yeast to trypticase soy broth enhances the growth of most strains of A.a (Sreenivasan et al.1993).

Aminoacids (Cystine and Thiamine) –Promotes the growth of all strains of A.a and results in a generation time comparable with that observed following the addition of 1.2% yeast extract. (Sreenivasan et al 1993).

Hormones –Steroid hormones including estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone are capable of enhancing the growth of A.a.

Iron –A.a expresses iron-binding proteins and has hemin binding activity. Furthermore, A.a down-regulates the expression of a 70 KDa membrane protein in iron-limited conditions.

pH –Optimum pH for the growth of Aa is 7.0-8.0, with optimum growth at 7.5. It is not commonly found in gingival pockets harboring acidogenic bacteria as it is inhibited at a pH of 6.5. (Sreenivasan et al 1993).

Salt concentration –A.a demonstrates optimal growth between 85.1 mEq/l and 170 mEq/l concentration of sodium.

Serotypes of A.a: [25-29]

Serotype -The type of organism determined by its constituent antigens.

King & Tatum (1962) - classified an Non-oral strains of A.a into 3 serotypes based on a heat-stable antigen.

Purvrer & Ko (1972) identified 24 different serogroups and 6 major agglutinating antigens of A. a using tube agglutination studies.

Taichman (1982) - used differences in surface antigens and leukotoxin production to classify A.a an into four serogroups.

Zambon (1983) - detected 3 serotypes of A.a and designated them as a, b & c. Similar to those of King & Tatum.

Saarela & Asiakainen (1992) extended to 5 types – a, b, c, d & e.

Serotype d, e, f, g: rarely found in oral samples.

Technique to determine Serotype-specific antigen: Indirect immunofluorescence (Zambon et al. 1983, Asikainen et al. 1991) with polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies (Gmür 1993), Immunodiffusion (Zambon et al. 1983, Saarela et al. 1992).

Genetic similarity:

Same individual & Same serotype – Genetically identical

Same individual & different serotype - Genetically non-identical

Different individuals & same or different serotypes - Genetically non-identical.

Natural Habitat of A.a: In humans highest levels of A.a in Periodontal pockets (Asaikainen et al. 1991, Slots J et al 1980, Wolff et al. 1985, Winkelhoff et al. 1986), Supragingival plaque & Oral mucosal surfaces (Muller et al. 1993, Van Steenbergen et al. 1993), Dorsum of tongue (Winkelhoff et al. 1986), Saliva (Slots J et al. 1990, Asaikainen et al. 1991), Pharynx (Van Steenbergen et al. 1993), Not recovered from edentulous babies (Frisken et al. 1990, Kohonen et al. 1992), Not recovered from edentulous older adults with few exceptions (Danser et al. 1995, Kohonen et al. 1991). Do not belong to the indigenous microbiota of any other body site but can cause non-oral infections (Finegold et al. 1993, Van winkelhoff et al. 1993).

Initial Colonization: A.a is one of the first colonizers on supragingival tooth surfaces in early plaque development in monkeys & in vivo models in humans (Killian et al. 1976). Suggests species can colonize healthy & clean oral cavities. Cultivable A.a occurs in atleast 10% of periodontally healthy children with primary dentition (Asaikainen et al. 1988).

Distribution Pattern:

A.a occurs only at isolated sites (Zambon et al. 1992, Haffajee et al. 1992). May be limited due to an antibody response.

IgG response to A.a is protective, able to limit infection (Lamster et al. 1998).

Antibody response limits A.a at the first erupting teeth in patients with LJP (Zambon et al. 1983).

Asaikainen S (1986) – older patients with LJP harbour a lower number of A.a +ve pockets than the young ones.

Baer P N 1971- LJP may burn out without treatment after the patients’s teenage years.

Rodenburg 1990 – Occurrence of A.a +ve sites decreases with age.

The prevalence of A.a decreases from 90% in the younger group to 40% in the older group (Rodenburg 1990).

Genetic Diversity of A.a: Discovery of A.a plasmids: The isolation of a plasmid from A.a was key in the constructing of intergeneric plasmids for the development of gene transfer systems. Plasmids in A.a were first documented from 10 clinical isolates derived from periodontal lesions of patients with rapidly destructive periodontitis. Other investigators have confirmed the presence of plasmids in A.a, although at a much lower frequency. Restriction endonuclease analysis indicated that strains within subjects were restricted to a single clonal type (Zambon et al. 1990). Restriction fragment-length polymorphism suggested a similarity of A.a strains within infected families (DiRenzo 1990).

Transmission of A.a:

Vertical Transmission- Similar strains of A.a are found in both parents & children (Asikainen et al 1996), Children harbour the same genotype of A.a (Prens et al 1994).

Horizontal Transmission –Siblings may harbour identical strains of A.a in their oral cavities (DiRenzo et al 1994, Tinoco et al 1998). Some studies however disagree (Prens et al 1994). Horizontal transmission can occur among adults or evidence by several studies in which married couples were used as models (Asikainen et al 1996).

Clinical Significance of Transmission- Recent evidence suggests the possibility that people with periodontitis may cause periodontal breakdown in their spouses (Von trail linden et al 1995). Spouses of deceased probands had more frequently deep periodontal pockets, attachment loss & periodontal pathogens than spouses of healthy probands (Von trail linden 1995).

Saliva & A.a: Higher the load of A.a in saliva greater is the risk of colonization of the recipient. Suppression of the micro-organisms from saliva may prevent their spread amongst the individuals. Periodontal treatment help suppress salivary A.a for at least 6 months (Van Trail Linden et al. 1995). Asikainen et al 1997- A.a strains from subgingival sites & saliva within the same individual were of the same serotype in 95% of 126 subjects. Saliva can be used as a representative sampling material in diagnosing of A.a (Van trail linden 1996).

Occurrence of A.a: Periodontally healthy children below 11 years of age showed an occurrence rate of 0-26% (Chen et al, Conrad et al). Holt et al 1994 reported a prevalence of subgingival A.a to be as high as 78% in healthy Vietnamese children [30]. Pre-pubertal periodontitis and other types of early-onset periodontitis – prevalence 40-100%. Adolescents with healthy periodontium are known to exhibit less than 15 % of subgingival A.a, while approximately 50% of adults with periodontitis shown subgingival presence of A.a (Asikainen et al). A.a prevalence was 75-100% in LJP lesions (Asikainen et al, Sweeney et al, Tinoco et al). Exceedingly high proportions of subgingival A.a in periodontal sites undergoing active breakdown – A.a ia a key bacterial pathogen in LJP. A.a was rarely isolated from healthy mucosal sites around integrated dental implants (Danser et al, Mengel et al, Mombelli et al). A.a was detected in failing dental implants and comprise major pathogens in infectious implant failure (Rosenburg et al 1991, Becker et al 1990). A.a can attach to barrier membranes. A.a implicated in failing regenerative periodontal therapy. Nowzari & Slots recovered A.a from a site demonstrating as little as 1mm of clinical attachment gain. Mattei et al- detected A.a in periodontal sites exhibiting suboptimal regeneration.

Persistence of A.a: Can survive in untreated, periodontal lesions for years. Russo et al 1998- stated A.a survived in 2 siblings for at least 23 yrs. Saarela et al 1999- subgingival colonization of A.a could persist for 11 yrs. Host defense of periodontium insufficient to eliminate organism from subgingival sites.

Misconceptions about A.a : [31]

A.a is a Late Colonizer: Early studies carried out on attachment of A.a on ATCC laboratory strains failed to demonstrate the natural aggregative capacity of A.a. Later on, Kolenbrander and his associates studied co-aggregation and suggested A.a was a poor colonizer since the ATCC strain Y4 showed co-aggregation with the universal co-aggregator i.e. Fusobacterium nucleatum. These microbial interactions with exception of A.a played a critical role in plaque formation. Thus, it was suggested that A.a was a late colonizer and incapable of participating in early plaque formation. Further, the discovery of Widespread Colonization Island (WCI) led to the understanding of the clinical adherence of bacterial phenotype in the laboratory. The WCI discovered WCI in 2001 that consists of 14 gene operons and mainly comprised of flp, tad and rcp genes that showed close relation of attachment to abiotic surfaces, aggregation and tight adherence. This discovery of WCI also influenced the change in the genus name from Actinobacillus to Aggregatibacter and demonstrated the importance of attachment for the survival of most primitive species. The fact that numerous pathobionts contain a functional portion of this island affirms the significance of adherence in their presence. It is known that A.a can adhere by both specific as well as non-specific mechanisms due to its inherent nature of binding to abiotic surfaces through the WCI along with binding via the outer membrane adhesins. Lastly, the discovery of an outer membrane adhesin, Aae showed higher specificity for oral epithelium. Unlike the WCI, Aae, binds in a highly specific dose-dependent manner to its receptor on buccal epithelial cells (BECs) [31,32].

Nutritional Fastidious nature of A.a : A.a is known for its fastidious nature requiring 5% CO2, serum and certain carbohydrates such as glucose constantly for its growth. The recovery of A.a from affected sites is ardous due its fastidious nature along with its slow and inconsistent growth after initial isolation. Recently, Brown and Whiteley in 2007 demonstrated A.a metabolizes lactate over any other carbohydrate sources owing to the presence of phosphoenol pyruvate- dependent phosphotransferase systems. Cultures showed decreased levels of lactate when cultured with glucose-consuming competitors like Streptococci. Further, it was concluded that A.a’s survival in lactic acid-rich culture was reduced competition with strains utilizing glucose as their carbohydrate source. Secondly, the addition of lactate to chemically defined media increased the growth of A.a in biofilms [31].

A highly aggregative non-motile microbe cannot escape from its biofilm habitat: Aggregation is a two-way street, on one side it forms a shield and protects the biofilm from environmental challenges whereas on the other it limits the capacity of the pathobiont to migrate to distant sites in cases of danger. Dispersin B (dspB) is a hexosaminidase attacking matrix polysaccharides consisting of a N-acetyl-D-glucosamine residues. Kaplan et al in 2003 discovered dspB. The discovery of dspB provided a mechanism for mobility leading to protection. A.a has now found out a way to balance its survival by achieving its nutrition through lactate-producing species and swiftly refraining from hazardous conditions by locomotion from products such as H2O2 formed by these lactate-producing species. 31,33-35.

A.a is the causative agent in LAP: Overcoming host restrictions (Suppressing Host defenses) : Leukotoxin (Ltx) is a known toxin that destroys leukocytes and lymphocytes. The toxin is known to neutralize local immune response and thus, unable other bacteria to overgrow. ApiA was the first discovered Outer Membrane Proteins (OMPS’s) in 1999 and is associated with the pathogenesis of Aggressive Periodontitis. The phenotype associated characteristic of ApiA include adhesion, invasion and complement resistance. Asakawa et al based on his work concluded that binding of factor H occurs between 100-200 amino acid sequences in the 295 ApiA amino acid protein. Similarly, the invasion and adhesion appears to occur in separate regions of the protein and this auto-transporter protein is known for its significant role in A.a’s survival and immune regulation. The serum exudate is the first to confront the microbial burden comprising of PMNs and complement that destroy bacteria by direct or indirect mechanisms. The PMNs engulf and thus degrade microbes at a rapid rate, similarly the complement acts directly on the cell wall of the bacteria causing holes in the outer membrane resulting in lysis of the cells. A.a is now known to regulate its host defense with 2 mechanisms: A.a possess ApiA which is a complement effector molecule and a leukotoxin that is known to destroy PMNs [31,36-38].

A.A In Non-Oral Infections: A.a is occasionally isolated from severe systemic infections (Zambon 1985, van Winkelhoff & Slots 1999).

Various systemic infections are:

Prosthetic-valve endocarditis (Pierce et al. 1984)

Pericarditis (Horowitz et al. 1987)

Septicemia (van Winkelhoff et al. 1993)

Pneumonia (Morris & Sewell 1994,

Infectious arthritis (Molina et al. 1994),

Abscesses in various body sites, such as brain, submandibular space, or hand (Salman et al.1986, Kaplan et al. 1989, Recently, periodontitis has been associated with Chronic coronary heart disease (Mattila et al. 1995, Beck et al. 1996), and A.a has been identified in atheromatous plaques in coronary arteries (Zambon et al. 1997).

Anti-Microbial Therapy for a.a Non-Oral Infections - Penicillins were the first choice, but had drawback of developing resistance- (Kujiper et al. 1992). A.a usually susceptible to amoxicillin, cephalosporins & ciprofloxacin but not to clindamycin- (Pajukanta et al, 1992). Saliva sample may be collected for in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing of A.a- (Slots J. 1980).

Virulence Factors of A.a : [39] Virulence factors are attributes of a micro-organism that enable it to colonize a particular niche in its host, overcome the host defenses and initiates a disease process. These factors frequently involve the ability to be transmitted to susceptible hosts. Increase in virulence factors means increase in pathogenicity.

A) Factors that promote colonization and persistence in the oral cavity:

i) Adhesins

ii) Invasins

iii) Bacteriocin

iv) Antibiotic resistance

B) Factors that interfere with Host defenses:

i) Leukotoxin

ii) Lipopolysaccharides (LPS)

iii) Cytolethal distending Toxin (CDT)

iv) Chemotactic Inhibitors

v) Immunosuppressive proteins

vi) Fc-binding proteins

C) Factors that destroy host tissues:

i) Cytotoxins

ii) Collagenase

iii) Bone resorption agents

iv) Stimulators of inflammatory mediators

v) Heat shock proteins

D) Factors that inhibit host’s repair:

i) Inhibitors of fibroblast proliferation

ii) Inhibitors of bone formation

Factors that Promote Colonization and Persistence In The Oral Cavity:

Adhesins : The bacterial surface components involved in adhesion are known as adhesins. They are proteinaceous structures found on the surface of the bacterial cell which interact and bind to specific receptors found in saliva, on the surface of tooth, on ECM proteins and on epithelial cells [40].

Adhesion of A.a to gingival crevice epithelium is probably the most important step in the colonization of this organism and subsequent destruction associated with periodontal disease. Cell surface entities adhere to fimbriae, extracellular amorphous material and extracellular vesicles.

Mechanism of virulence: Fimbriae carry Curlin proteins and adhesins which attach them to the substratum so that the bacteria can withstand shear forces and obtain nutrients. Therefore, strains possessing fimbriae adhere 3-4 folds onto the tooth surface better than non-fimbriated variants.

No specificity for saliva-coated v/s uncoated hydroxyapatite: suggests that binding to components in the salivary pellicle does not play a role in its adhesive characteristics.

Adhesion of A.a to epithelial cells: Bacteria accrete by means of aggregation, intrageneric and intergeneric co-aggregation and interactions with distinct and bacteria-specific salivary binding molecules. Epitheliotoxin aids in penetrating the sulcular epithelium. All A.a strains tend to clump and form chains. Surface ultrastructure entities such as extracellular amorphous material and vesicles mediate the aggregation. To date, intergeneric co-aggregation by A.a has been demonstrated only with Fusobacterium nucleatum.

Tooth: The adhesion of A.a to the gingival crevicular epithelium is the most important step in the colonization of this organism and the subsequent destruction associated with periodontal disease. Fimbriated strains show 3-4 fold better adherence (Rosan et al. 1988)

Epithelium: Most of the A.a strains adhere strongly to the epithelial cells. Lactoferrin iron levels affect attachment of A.a to buccal epithelial cells (Fine & Furgang et al 2002). Also, Iron binding protein may interfere with binding of A.a to host cells while degree of iron saturation of lactoferrin might play a role in these interactions.

Extracellular Matrix: In order to initiate disease in extraoral sites A.a must bind to the ECM. Major component of ECM is collagen. A.a binds to collagen type I, II, III, V but not to type IV. It does not bind to any of the collagens in soluble form but, instead binds to insoluble forms which aid in spread and colonization.

Invasins : [41] Invasion is a dynamic process with bacteria appearing in the host cell cytoplasm within 30 minutes. Invasion mechanism is initiated when A.a makes contact with the microvilli of the cells and is translocated to the surface of the cell. It is rapid mechanism involving the formation of cell-surface ‘craters’ or apertures with lip-like rims. These invasins occur as indentations on the cell-surface, as well as in membrane ruffles where they appear to be entering into epithelial cells.

Studies by Meyer et al 1997 suggested that there are primary and secondary receptors that help A.a in invasion. The primary receptor is the transferrin receptor while secondary receptors are the integrins & transmembrane proteins. De novo protein synthesis by both bacteria & the cells is required for invasion to take place. Microbial uptake by the cells depends on the rearrangement of the host cytoskeleton suggesting a role for actin in the invasion process. Actin is transported from the periphery of the cell to a focus surrounding the bacterium.

Invasion of epithelial cells by A.a : Attachment of organisms to the host cell with initiation of some form of signaling, Binding to a receptor, Entry in a vacuole, Escape from the vacuole, Rapid multiplication, Intra-cellular spread. A short time after escape from the vacuole into the cytoplasm it transits through the cell to neighboring cells via bacteria-induced protrusions that appear to be extensions of the host cell membrane.

Bacteriocin (Gibbons1989): [42]

Bacteriocins are the proteins, lethal in nature that are produced by bacteria.

Structure and composition: Bacteriocins are heterogenous group of particles with different morphological and biochemical entities. They range from a simple protein to a high molecular weight complex of proteins.

Mechanism of virulence: Is to increase the permeability of the cell membrane of target bacteria, which leads to leakage of DNA, RNA & macromolecules essential for growth.

Lima et al, isolated a bacteriocin named Actinomycetemcomitans from A.a P (7-20) strain that is active against Peptostreptoccus anaerobius ATCC 27337.

Actinobacillin, a bacteriocin produced by A.a is active against Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus uberis and Actinomyces viscosus, has been identified and purified. It also results in alteration of cell permeability of certain target bacteria causing leakage of DNA, RNA and other intercellular molecules required for growth.

Antibiotic Resistance: [43]

Antibiotics have been and continued till date, to be used effectively in the treatment of periodontal infections. However, certain organisms develop potential for antibiotic resistance.

Reason for resistance: Poor permeability of the outer membrane is responsible for the antimicrobial resistance in Gram negative organisms. Antimicrobial resistance of a pathogen could be associated with its virulence. Antimicrobial resistance may promote the persistence of a pathogen in the infected host during antimicrobial treatment and lead to prolonged or life-threatening infections. Resistance may also contribute to the quick and unlimited spread of a pathogen in a population.

Mechanism of virulence: Approximately 30% of oral A.a are resistant to benzyl-penicillin. New or altered penicillin-binding proteins on the bacterial cell surface may account for the non-enzymatic penicillin resistance of A.a. Tetracyclines, as an adjunct to mechanical debridement, is the most commonly employed antibiotic in treating LJP.

In a study by Zambon JJ (1983), 82% of 19 clinical isolates of A.a were found resistant to tetracyclines and carried the tetB resistance determinant. Moreover, the tetB determinant was capable of being transferred by conjugation of other A.a strains and to H influenza. These data suggests that, the antibiotic resistance in A.a is on the rise and likely to be responsible for treatment failures in the future.

Factors that Interfere with Host’s Defense : Leukotoxin [44-47]

One of the most studied virulence factor of A.a is Leukotoxin. This toxin is a 116 kDa immuno-modulating protein produced by 56% of strains isolated from LJP patients.

Location : It is proteinaceous toxin secreted from the cell membrane of A.a.

Structure and composition : A.a leukotoxin is a member of RTX (Repeats in ToXin) family of toxin that produces pore-forming hemolysins or leukotoxins (Lally et al. 1989).

Gene operon that produces A.a leukotoxin is named as ltx. The leukotoxin operon consists of four coding genes named as ltxC, ltxA, ltxB, ltxD and an upstream promoter gene.

ltxA : encodes the structure of the toxin.

ltxC : encodes for components required for post-translational acylation of the toxin.

ltxB and ltxD : encodes for transport of the toxin to the bacterial outer membrane.

Leukotoxin consists of 1,055 amino acids encoded by the leukotoxin gene in the leukotoxin operon.

Mechanism of virulence: Leukotoxin is not only species-specific but also cell-specific. The toxin binds to neutrophils, monocytes and a subset of lymphocytes; & forms pores in the membranes of these target cells overwhelming their ability to sustain osmotic homeostasis, resulting in cell death [48].

Interaction with PMNs: Leukotoxin has been shown to efficiently cause the death of human PMNs through the extracellular release of proteolytic enzymes from both primary & secondary granules, along with activation and release of MMP-8, which contributes to periodontal tissue destruction.

Interaction with lymphocytes: The leukotoxin’s ability to induce apoptosis within lymphocytes might result in impaired acquired immune response of periodontal infections. A shift in the balance between Th-1 and Th-2 subsets of T cells is seen in inflamed periodontal tissues, while the Th-2 cells commonly associated with chronic periodontitis. Its ability to affect the lymphocytes indicates a possible role of this molecule in Th-1/Th-2/Th-17 differentiation, important in inflammatory pathogenesis.

Interaction with monocytes/ macrophages: Leukotoxin causes the activation of caspase-1, which is a cytosolic cysteine proteinase that specifically induces activation & secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, which result in monocyte/macrophage lysis by incorporation in a cytosolic multimer complex named the inflammasome.

JP2 phenotype of the A.a strains produces high levels of leukotoxin. The leukotoxin is not only species-specific but also cell-specific. A A.a leukotoxin is specific for cells that express B2-integrin & LFA-1. The toxin binds to neutrophils, monocytes & forms pores in the membrane of these cells. The pores induced in the cells overwhelm the ability of the cell to sustain osmotic homeostasis, resulting in cell death. A.a leukotoxin induces apoptosis or necrosis in a dose-dependent manner. At high concentration, the toxin binds non-specifically to cell-membranes forming large pores allowing the rapid influx of Ca2+ and loss of ATP, resulting in necrosis. While at low concentration, the toxin binds to specific cell-surface proteins on susceptible cells & forms small diameter pores, allowing the uncontrolled influx of Na+ and the activation of apoptosis [49].

Iron Transport System: Iron plays an important role in regulation of virulence factors of A.a. Willemsen et al. 1997 identified an afuA gene in A.a and proposed that its product plays an important role in the periplasmic transport of iron into the cell. Rhodes et al. 2005 identified afe ABCD iron transport system in A.a and found that Afe protein functions in iron acquisition in A.a & a heterozygous host E.coli. The ability to obtain iron is an essential function for a bacterium to be pathogenic. Hayashida et al. 2002 reported that most strains of A.a could utilize hemoglobin as an iron source, with the only exception being highly leukotoxic strain serotype strains. He also showed that highly leukotoxic strains harboured a defective hgpA gene, which normally encodes hemoglobin binding protein A. Leukotoxin can lyse the human erythrocytes. (Bhattacharjee et al. 2001). The genome of A.a strain HK1651 contains a homolog of hgpA which encodes hemoglobin binding protein A (Actis et al. 2003). Some strains of A.a are able to utilize human hemoglobulin as an iron source [50,51].

Lipopolysaccharides: [52,53]

Are endotoxins having a high potential for causing destruction of an array of host cells and tissues (Hitchcock et al 1986). It causes bone resorption, platelet activation & activates macrophages to produce IL-1 & TNF-α.

Structure and composition: it comprises of 3 parts:

1) O antigen: is the basis of antigenic variation among many G-ve pathogens which confirms the existence of multiple serotypes.

2) Core oligosaccharide: It allows organisms to adhere to epithelial tissues & provide protection from damaging reactions with antibody and components.

3) Lipid A: It exerts its toxic effects when released from multiplying cells, or when the bacteria are lysed. In monocytes & macrophages it results in production of IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α & Platelet activating factor; activation of the complement & coagulation cascade. Low concentration of A.a lipopolysaccharide stimulates macrophages to produce IL-1 α, IL-1 β & TNF, cytokines involved in tissue inflammation & bone resorption. (Saglie et al, 1990). LPS may also contribute to destruction of periodontal connective tissue by activating the pathways that lead to stimulation of MMPs & plasminogen activator. Recently, A.a LPS has shown to induce foam cell formation & cholesteryl ester accumulation in murine macrophages which suggests that it also has pro-atherogenic activity.

Cytolethal Distending Toxin (CDT): [54,55]

CDT of A.a is a newly described cytotoxin with immunosuppressive properties.

Location: CDT is a cell cycle-modulatory protein i.e secreted freely or associated with the membrane of the producing bacteria.

Structure & composition: CDT is a tripartite structure encoded by a locus of 3 genes, Cdt ABC. The toxin itself is encoded by CdtB while CdtA and CdtC appear to encode proteins that mediate interaction between the Cdt complex and the host cell surface.

Mechanism of virulence: The active subunit, CdtB, exhibits DNase I activity. While CdtA and CdtC possess putative mucin-like carbohydrate binding domains that predict interaction with the host cell surface. CdtB is transported to the nucleus where it causes DNA damage through its DNase activity resulting in apoptosis, through its caspase activation. Cdt disrupts macrophage function by inhibiting phagocytic activity as well as affecting the production of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8. It was found that Cdt is largely responsible for the inhibition of proliferation of human PDL cells & gingival fibroblasts. In human gingival fibroblasts, Cdt is able to stimulate the production of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kβ ligand which may be involved in pathological bone resorption, characteristic of LAP. [56].

Chemotactic Inhibitors (Van Dyke 1982): Host’s first line of defense against invading bacteria is the recruitment of phagocytes by chemotaxis. This process, known as chemotaxis, involves a number of steps, including the binding of chemotactic agents, upregulation of adhesin receptors, binding to the endothelium & movement of the phagocytic cells into the underlying tissues. The ability to disrupt chemotaxis permits the invading organism to survive this major challenge from the host. A.a secretes a low molecular weight compound that inhibits polymorphonuclear leucocyte chemotaxis. The inhibitory activity is abrogated by treatment with proteinase K, suggesting that the compound is proteinaceous in nature. Another activity of PMNs is the killing of bacteria by a wide variety of potent antibacterial agents. A heat-stable protein in A.a inhibits the production of H202 by PMNs & many strains are naturally resistant to high conc of H202. Furthermore, A.a also has been shown to be resistant to several of the cationic peptides, known as defensins that are found in neutrophils.

Immunosuppressive Factors (Shenker et al 1982, 1990):

A.a has been shown to elaborate many factors capable of suppressing host defense mechanisms.

A.a produces a protein that inhibits DNA, RNA & protein synthesis in mitogen activated human T cells. (Shenker et al 1982)

A 60-kDa protein secreted by A.a has been purified & shown to inhibit IgG and IgM synthesis by human lymphocytes. It affects immunoglobulin production by activating B cells that downregulate the ability of B and T cells to respond to mitogens. Mice injected with A.a exhibit diminished ability to respond to E.coli lipopolysaccharide. Furthermore, these mice do not make antibodies to A.a for an extended period

Fc Binding Proteins (Mintz et al 1990):

Location: Fc binding proteins are found to be associated with the bacterial cell surface & are released in soluble form during bacterial growth.

Mechanism of virulence: Fc region of an antibody molecule is important in the binding of the antibody to specific receptors on PMNs. If other proteins compete for binding to this region of PMNs, binding of the antibody may be inhibited & thereby, inhibit phagocytosis.

Tolo & Hegland (1991) demonstrated that molecules on the surface of A.a that are associated with capsular material & secreted into the medium bind to the Fc portion of IgG; the binding inhibits the ability of opsonizing antibodies to bind PMNs and reduces phagocytosis by 90%. Also, the Fc receptors are known to play an important role in complement activation.

Factors That Destroy Host Tissues:

Cytotoxin: One of the most important cell types within the gingival connective tissue is the fibroblasts. Fibroblasts are major source of collagen & confer a structural integrity to the tissue. A.a produces heat labile cytotoxin i.e cytotoxic to fibroblasts & which is known to inhibit fibroblasts proliferation. The toxin is considered a virulence factor due to its impact on fibroblasts viability. Mechanism of virulence – One toxin i.e secreted into supernatant has been isolated & identified as a 50-kDa protein that inhibits DNA synthesis in the fibroblasts. Another surface-associated material cytotoxin, designated Gapstein, is an 8-kDa protein. The inhibition of fibroblasts growth may be expressed as a decrease in collagen synthesis which is manifested as a loss of collagen synthesis in certain forms of juvenile periodontitis [57].

Collagenases: Collagen is the most abundant constituent of the extracellular matrix. A major feature of periodontal disease is a marked reduction in gingival collagen fibre density. Collagenase activity is associated with two important periodontal pathogens, A.a & P.g.

Mechanism of virulence: Collagenases are endopeptidases/extracellular proteolytic enzymes secreted by bacteria that digest nearly all collagen fibres in their insoluble triple helical form. Proteolytic enzymes in A.a have been reported to degrade IgG, serum IgA & IgM but not IgD or IgE. This results in dysregulation in host’s immune response.

Heat Shock Proteins (HSP): [58]

HSPs are produced as a protection against stress (Ellis 1996), but they also play a role under normal conditions during the cell cycle, development, and differentiation (Bukau & Horwich 1998). HSPs may additionally function as molecular chaperones ensuring that protein assembly into higher order structures occurs correctly (Ellis 1996).

Mechanism of virulence: A.a strains have shown presence of HSPs, including GroEL-like (HSP-60) & DnaK-like (HSP-70) proteins. Proteins homologous to GroEL-like HSP is osteolytic. Purified native GroEL-like HSP from A.a promotes epithelial cell proliferation at lower HSP concentration, but has a toxic effect on epithelial cells at higher HSP concentrations.

Several authors have reported in A.a the presence of HSPs, including GroEL-like (HSP60) and DnaK-like (HSP70) proteins (Koga et al. 1993, Løkensgaard et al. 1994, Nakano et al. 1995, Hinode et al. 1998, Goulhen et al. 1998).

Bone Resorption Agents: A.a has been shown to stimulate bone resorption by several different mechanisms: lipopolysaccharide, proteolysis-sensitive factor in micro vesicles & surface associated material – all of which in turn inhibit osteoblast proliferation. They cause activation of bone resorption & induction of osteoclasts proliferation. A.a LPS, is a very effective bone resorption mediator, & has been shown to cause the release of calcium from fetal long bones in the Ca2+ fetal bone resorption assay.

Stimulators of Inflammatory Mediators: Leukotoxin from A.a has been shown to induce MMP release & activation from neutrophils in a dose dependent manner. An extracellular 37kDa antigenic glycoprotein from A.a (serotype b) has been shown to have ability to induce the release of cytokines from murine macrophages. It induces strong TNF-α, IL-1β & IL-6.

Factors that Inhibit Host’s Repair: Constitute factors that inhibit fibroblasts proliferation & factors that inhibit bone formation. A.a produces 8kDa antigen which suppresses proliferation of fibroblasts, monocytes & osteoblasts.

Impact of A.a on Immune System: [59-66]

Inhibition of PMN Function: A.a secretes a low molecular weight compound that inhibits PMN chemotaxis. The ability to disrupt chemotaxis permits the invading organism to survive this major host challenge. Almost all aspects of PNM function are impaired starting with Chemotaxis: is the directional movement of the PMN towards a invading antigen. Then the fusion of lysosome into the phagocytosed vesicle, and even the oxidative killing process of the PMN is affected. May be due to competition with one of the chemo attractants NFMP (chemotaxis) (N-formyl-methionylleucyl-phenylalanine. Inhibit the fusion of PMN with lysosomes thus resist the antibacterial action of these agents. A heat stable protein in AAC inhibits the production of H2O2 by PMN and many strains are naturally resistant to high conc of H2O2. They are also resistant to defensins - Priming of PMNs: FcγIIIr receptor is to be a very important factor for the priming of the neutrophils, this FcγIIIr receptor was found to be deficient in 6 case studies of JP. The leukotoxin: known to produce a toxin which has the capacity to kill both myeloid and lymphoid leukocytes. They inhibit LFA-1 production. LFA-1 which are secreted by myeloid and lymphoid cells and are known to mediate important immune functions like endothelial transmigration and antigen presentation via MHC class I & II molecules. This may be one of the main causes for immunosuppression.

Oxidative Killing Mechanism of PMN: In the PMNs its observed that the myeloperoxidase system is the one that actually kills the organism more than the H2O2. It has been estimated that about two-thirds of the killing of A.a by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes under normoxic conditions is mediated by the myeloperoxidase system, and that this system accounts for most of the oxidative killing. The bactericidal activity of myeloperoxidase is dependent upon two functions. First, the phagocyte must be able to form sufficient substrate H2O2 via the respiratory burst pathway. Thus, the phagocyte must be in the presence of dissolved dioxygen. Second, the phagocyte must be able to secrete the myeloperoxidase into the vicinity of the microorganism (therefore, the phagocyte must be capable of phagosome-lysosome fusion).

Non- Oxidative Mechanism of PMN: α-Defensins although are found to be active against a lot of periodontopathic bacteria the A.a are found to be relatively resistant to these. The α-helical peptide was found to be very effective in killing the A.a LL-37 with the 99percentage effectivity. Cathepsin G is found to be very effective in handling A.a i.e microbicidal both by enzyme dependent and independent pathway. Other enzymes may be Apolactoferrin is also microbicidal it may function by binding to metals and causing a defect in the membrane. Membrane disruptive proteins like chaotropic ions. Inhibitors of PMN Function: A.a secretes a low-molecular weight compound that inhibits polymorphonuclear leukocyte chemotaxis. A heat-stable protein in A.a inhibits the production of H2O2 by PMNs. Many strains are naturally resistant to high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. A.a has been shown to be capable of inhibiting polymorphonuclear leukocytes from producing some of the antibactericidal compounds, and it is intrinsically resistant to others. A.a has been shown to be resistant to several of the cationic peptides, such as defensins, found in neutrophils. Monocyte/Macrophage Response to A.a: Monocytes exhibit susceptibility to A.a leukotoxin similar to that described for PMN’s. Leukotoxin acts within 5 seconds to promote Ca influx into neutrophils & HL-60 cells (monocytes cell line) which is followed by death within 10-15mins (Taichmann et al 1991). Serotype specific polysaccharide Ag induces the release of IL-1, IL-6 & TNF-α. Exposure of monocytes to A.a organisms stimulate the release of TNF (LT. deman /Economen 1988). Evidence demonstrates that A.a promotes monocyte apoptosis (programmed cell death). This is promoted through interaction with the lipopolysaccharide receptor of CD-14 positive macrophages. Produces a potent but heat-labile leukotoxin capable of killing monocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Reddi et al reported that cell surface protein isolated from A.a stimulates interleukin-6 synthesis from monocytes and IL-1 from macrophages. A.a lipopolysaccharide were shown to stimulate tumor necrosis factor and interleukin- 1 release from monocytes. Nishihara et al. reported that A.a lipopolysaccharide stimulated interleukin-1 inhibitor secretion from macrophages. The interleukin-1 inhibitor decreased osteoclast-mediated bone resorption in organ culture and inhibited the osteoclast like cell formation in mouse marrow cultures, suggesting that the interleukin-1 inhibitor may counter the connective tissue and bone destructive activities of interleukin-1 in periodontal disease. Additional evidence demonstrates that A.a promotes monocyte apoptosis (programmed cell death). Humoral Immune Response: Functional properties of antibodies against A.a are: Inhibition of adhesion & invasion, Complement activation, Neutralization of leukotoxin, Opsonization & phagocytes. Proteases produced by A.a cleave IgG, IgA & IgM. Ebersole et al 1980 – showed an association between increased frequency of antibody to A.a serotype b in 90% of L-EOP patients, but only 40% of G-EOP patients & 25% of adult periodontitis patients. Clinical Implication of Humoral Immune Response: Diagnostic potential of antibody against periodontopathic bacteria: numerous clinical and immunological studies have demonstrated the diagnostic potential of patient sera. ELISA is probably most widely used assay. Co-relation between serum antibody and periodontitis therapy: Ebersole et al showed that the antibody titre for A.a after scaling. This finding suggests that a humoral immune response may be a major factor in the clinical improvement observed after treatment. Immune responses as markers of susceptibility of periodontal diseases: Biological functions of antibodies such as IgG subclasses are implicated in the progression of periodontal diseases. Assessment of those functional characteristics may have diagnostic value in defining susceptibility to periodontal disease. Diagnostic Modalities for A.a: Socransky SS 1992, Haffajee AD 1992 introduced a 2 step procedure involving Culture + Nucleic acid based detection that improves detection limit. Immunodiagnostic Methods employ Antibodies that recognizes specific bacterial antigens to detect target micro-organism, do not require viable bacteria, less susceptible to variations in sample processing, less time consuming, easier to perform than culture. Bonta et al 1985 - detected A.a by Indirect immunofluorescence Method for detection of A.a, detection limit of 500 cells/ml, sensitivity-82-100% and specificity – 88-92%. Slots et al 1985 - detected A.a by Immunofluorescence Method and compared with culture method. Sensitivity -77% and specificity – 81%. Evalusite Test : Eastman Kodak Company (Rochester NY), commercially developed, Antibody-based sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection of A.a, assay showed detection limit of 105 A.a cells, Assay only detected 4 of 20 culture positive samplessensitivity of 20 %. Nucleic acid probes have radiolabeled DNA probes for A.a based on 165 rRNA genes with detection limit of 1000 cells , also show no evidence of cross-reactivity. Wolff et al 1992 in his study found concentrate A.a in specimen followed by immunofluorescence labelling and detection of cells with monoclonal antibody to whole cell antigens, assay showed a detection limit of 104 cells, sensitivity – 100%, specificity – 68%.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR Assay): Potential for being ideal detection method of periodontal micro-organisms, easy to perform, excellent detection limits, very little cross-reactivity under optimal conditions, detects levels of pathogens too low to be of clinical significance. Chen & slots 1996- PCR assays for detection of A.a using primers to 16S rRNA signature sequences. No cross reactivity with non-target organisms. Detection limit of 25-100 cells. Sensitivity- 45%, specificity- 79%. Furcht 1996- described PCR assay using primers to 16S rRNA genes of A.a. Detection limit of 10 cells. May be used to distinguish individual genotype of the species. Flemming 1996 – PCR detection of leukotoxin gene, detection limit of 1000 cells/ml or 15 cells per 15 ul of sample in a PCR reaction mixture, According to direct PCR method- sensitivity-65% and specificity 89%. Tran and Rudney 1996 – Multiplex PCR assay, targeting 16S Rrna genes, showed detection limit of 2 A.a cells. Possible Reasons for Limitation of Destruction to Certain Teeth: Zambon (1985) reviewed the relationship of A.a to periodontal disease. The possible reasons for the limitation of periodontal destruction to certain teeth are: After initial colonization of the first permanent teeth to erupt (the first molars and incisors), A.a evades the host defenses by different mechanisms, including production of polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) chemotaxis inhibiting factors, endotoxin, collagenases, leukotoxin, and other factors that allow the bacteria to colonize the pocket and initiate the destruction of the periodontal tissues. After this initial attack, adequate immune defenses are stimulated to produce opsonic antibodies to enhance the clearance and phagocytosis of invading bacteria and neutralize leukotoxic activity. In this manner, colonization of other sites may be prevented strong antibody response to infecting agents is one characteristic of LAP. (Zambon et al 1983). [67-68] 1. Bacteria antagonistic to A.a may colonize the periodontal tissues and inhibit A.a from further colonization of periodontal sites in the mouth. This would localize A.a infection and tissue destruction. (Hillman 1982). 2. A.a may lose its leukotoxin producing ability for unknown reasons. If this happens, the progression of the disease may become arrested or impaired, and colonization of new periodontal sites may be averted. (Slots 1982). 3. A defect in cementum formation may be responsible for the localization of the lesions. Root surfaces teeth extracted from patients with LAP have been found to have hypoplastic or aplastic cementum. This was true not only of root surfaces exposed to periodontal pockets, but also of roots still surrounded by their periodontium. (Page et al 1985). Prevention And Control of Periodontitis Caused by A.a: [69-72]. 1. Alter subgingival environment reduction in probing depth mechanical removal or disruption of subgingival plaque biofilm application of oxygenating and redox agents 2. Replacement therapy pre-eruptive colonization competitive replacement Reduction in probing depth : Surgical or non-surgical therapy has been successful in the treatment of periodontal disease, achieving an immediate ecological change that favors a facultative anaerobic gingival microflora and depriving the subgingival microflora of its anaerobic environment at the base of the deep pockets which is mandatory for the reducing growth of A.a. Mechanical removal or disruption of subgingival biofilm changes the ecology and the remaining micro-organisms become accessible to both host factors and antimicrobial agents. Use of antimicrobials by local application of oxygenating and redox agents. Although the use of redox agents does not release oxygen, the dyes can raise the redox potential of an ecosystem. The dye most commonly used is methylene blue. Replacement therapy: Phenomenon by which one member of the ecosystem can inhibit the growth of another is termed as bacterial interference. Use of antagonistic organism to control pathogens and prevent disease is termed replacement therapy. The Main approaches to the use of replacement therapy to prevent periodontal disease are: 1. Pre-eruptive colonization: Ecological niches within the plaque are filled by a harmless or potentially beneficial organism before the undesirable strain has had the opportunity to colonize. 2. Competitive displacement: here, a more competitive strain would displace a pre-existing organism from plaque. In health, it has been shown that H2O2 producing strains of Streptococcus sanguis inhibit the growth of A.a, whereas the converse is true for plaque from sites with LAP. Effect of Periodontal Therapy on Subgingival A.a : A.a may survive in untreated periodontal lesions for a considerable period of time. Slots and Rosling, 1983, showed that scaling and root planning alone was unable to remove Aa from LJP lesions. Failure of non-surgical therapy to effectively control A.a from gingival sites may result in the ability of organisms to invade gingival tissue and thereby evade the effect of mechanical debridement and periodontal healing. Periodontal surgery often fails to control effectively subgingival A.a. Resective periodontal surgery is more effective than access flap surgery in combating subgingival A.a. Systemic antibiotics have the potential to eradicate A.a residing in the periodontal pockets and gingival tissues. Slots et al, 1983, combined the use of tetracycline with SRP or with periodontal flap surgery and found that the levels of Aa was markedly suppressed in LJP lesions. Compared to systemic antibiotic therapy, topical periodontal drug therapy substantially reduces adverse patient reactions and antimicrobial resistance. However, topical subgingival application of antimicrobials have largely been unsuccessful in eradicating subgingival A.a. A.a & Dental Caries: Intra-oral equilibrium between Cariogenic species and Periodontopathogens - Both Streptococci and Actinomycetes group of organisms are facultative anaerobes, & doubling time for microbial populations during the first four hours of development are less than one hour. S. mutans will infect the hard tissues of the teeth by fermentation and result in acid products. S. mutans have some characteristics such as the ability to attach to the enamel surface, produce metabolicity, and the ability to form biofilms producing extracellular polysaccharides substance (EPS) and these properties support the occurrence of dental caries [73-77]. A.a & Viruses: A proposed viral-bacterial paradigm (Slots 2010) – LAP lesions may be associated with high genome copy counts of herpes viruses, suggesting their involvement in course of disease. Herpes virus, CMV & EBV- induce periodontal destruction (Slots 2015). CMV also known to increase cellular susceptibility for bacterial adherence (Teughels, Sliepen, Quirynen 2007).

A.a and Implant Failure: Presence of microbial plaque is a major factor associated with peri-implant health and as a result, stringent plaque control measures should be carried out to refrain peri-implant diseases. Implant failure is also associated with numerous factors like interaction of physiochemical implant surfaces with subgingival microflora and underlying periodontal tissues. Certain pathogens like P gingivalis, T denticola, T forsythia, A.a, Prevotella intermedia and Campylobacter species have been associated with peri-implant health as well as peri-implant disease [78-80]. As a result, routine evaluation of microbiological parameters is equally essential for maintaining periimplant health. A recent systematic review by Sahrmann et al 2020 assessed 28 studies using PCR based methods and 19 studies for meta-analysis reviewed a higher prevalence of A.a and P.g in peri-implantitis biofilms compared with healthy implants [81]. Recent Studies Showing Co-Relation between A.a and Severity of Periodontitis: Puletic et al. 2020 conducted a study to detect rates of P.g, T. forsythia, P intermedia & A.a) and Herpes viruses (HSV-1), CMV, EBV in different forms and severity of periodontal disease and to compare them with those of periodontally healthy subjects. 129 patients got divided into Four groups – Periodontal abcess group (39 pts), NUP group (33 patients), Chronic periodontitis group (27 patients) and Healthy patients group (30 pts). Further samples collected from only active periodontal sites and detected with PCR. Results revealed - ↑ in P.g, T forsythia, P intermedia, in all except healthy groups, A.a was seen highest in chronic periodontitis group than other two groups. Occurrence of EBV ↑ in NUP than in CP pts & healthy pts. CMV was significantly more in PA, NUP than in CP & Healthy pts. Moderate and severe periodontitis pts showed ↑ rates of EBV & CMV in all forms of periodontitis pts [82].

The treatment and prevention of periodontal infections is an ecological problem. No matter which preventive or treatment regime is employed, a microbiota will re-establish after that modality. The microbiota might be host-compatible or it may have the potential to cause damage to the host. The therapy goals should be to eliminate pathogenic species and retain or foster species compatible with, or beneficial to the host. Thus, it is essential to carefully evaluate what current therapies do to the microbiota and to develop new tools to modulate the host-bacterial ecological relationship and to predictably control the supragingival and subgingival ecosystem.

Clearly Auctoresonline and particularly Psychology and Mental Health Care Journal is dedicated to improving health care services for individuals and populations. The editorial boards' ability to efficiently recognize and share the global importance of health literacy with a variety of stakeholders. Auctoresonline publishing platform can be used to facilitate of optimal client-based services and should be added to health care professionals' repertoire of evidence-based health care resources.

Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Intervention The submission and review process was adequate. However I think that the publication total value should have been enlightened in early fases. Thank you for all.

Journal of Women Health Care and Issues By the present mail, I want to say thank to you and tour colleagues for facilitating my published article. Specially thank you for the peer review process, support from the editorial office. I appreciate positively the quality of your journal.

Journal of Clinical Research and Reports I would be very delighted to submit my testimonial regarding the reviewer board and the editorial office. The reviewer board were accurate and helpful regarding any modifications for my manuscript. And the editorial office were very helpful and supportive in contacting and monitoring with any update and offering help. It was my pleasure to contribute with your promising Journal and I am looking forward for more collaboration.

We would like to thank the Journal of Thoracic Disease and Cardiothoracic Surgery because of the services they provided us for our articles. The peer-review process was done in a very excellent time manner, and the opinions of the reviewers helped us to improve our manuscript further. The editorial office had an outstanding correspondence with us and guided us in many ways. During a hard time of the pandemic that is affecting every one of us tremendously, the editorial office helped us make everything easier for publishing scientific work. Hope for a more scientific relationship with your Journal.

The peer-review process which consisted high quality queries on the paper. I did answer six reviewers’ questions and comments before the paper was accepted. The support from the editorial office is excellent.

Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. I had the experience of publishing a research article recently. The whole process was simple from submission to publication. The reviewers made specific and valuable recommendations and corrections that improved the quality of my publication. I strongly recommend this Journal.

Dr. Katarzyna Byczkowska My testimonial covering: "The peer review process is quick and effective. The support from the editorial office is very professional and friendly. Quality of the Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on cardiology that is useful for other professionals in the field.

Thank you most sincerely, with regard to the support you have given in relation to the reviewing process and the processing of my article entitled "Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of The Prostate Gland: A Review and Update" for publication in your esteemed Journal, Journal of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics". The editorial team has been very supportive.

Testimony of Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology: work with your Reviews has been a educational and constructive experience. The editorial office were very helpful and supportive. It was a pleasure to contribute to your Journal.

Dr. Bernard Terkimbi Utoo, I am happy to publish my scientific work in Journal of Women Health Care and Issues (JWHCI). The manuscript submission was seamless and peer review process was top notch. I was amazed that 4 reviewers worked on the manuscript which made it a highly technical, standard and excellent quality paper. I appreciate the format and consideration for the APC as well as the speed of publication. It is my pleasure to continue with this scientific relationship with the esteem JWHCI.

This is an acknowledgment for peer reviewers, editorial board of Journal of Clinical Research and Reports. They show a lot of consideration for us as publishers for our research article “Evaluation of the different factors associated with side effects of COVID-19 vaccination on medical students, Mutah university, Al-Karak, Jordan”, in a very professional and easy way. This journal is one of outstanding medical journal.

Dear Hao Jiang, to Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing We greatly appreciate the efficient, professional and rapid processing of our paper by your team. If there is anything else we should do, please do not hesitate to let us know. On behalf of my co-authors, we would like to express our great appreciation to editor and reviewers.

As an author who has recently published in the journal "Brain and Neurological Disorders". I am delighted to provide a testimonial on the peer review process, editorial office support, and the overall quality of the journal. The peer review process at Brain and Neurological Disorders is rigorous and meticulous, ensuring that only high-quality, evidence-based research is published. The reviewers are experts in their fields, and their comments and suggestions were constructive and helped improve the quality of my manuscript. The review process was timely and efficient, with clear communication from the editorial office at each stage. The support from the editorial office was exceptional throughout the entire process. The editorial staff was responsive, professional, and always willing to help. They provided valuable guidance on formatting, structure, and ethical considerations, making the submission process seamless. Moreover, they kept me informed about the status of my manuscript and provided timely updates, which made the process less stressful. The journal Brain and Neurological Disorders is of the highest quality, with a strong focus on publishing cutting-edge research in the field of neurology. The articles published in this journal are well-researched, rigorously peer-reviewed, and written by experts in the field. The journal maintains high standards, ensuring that readers are provided with the most up-to-date and reliable information on brain and neurological disorders. In conclusion, I had a wonderful experience publishing in Brain and Neurological Disorders. The peer review process was thorough, the editorial office provided exceptional support, and the journal's quality is second to none. I would highly recommend this journal to any researcher working in the field of neurology and brain disorders.

Dear Agrippa Hilda, Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery, Editorial Coordinator, I trust this message finds you well. I want to extend my appreciation for considering my article for publication in your esteemed journal. I am pleased to provide a testimonial regarding the peer review process and the support received from your editorial office. The peer review process for my paper was carried out in a highly professional and thorough manner. The feedback and comments provided by the authors were constructive and very useful in improving the quality of the manuscript. This rigorous assessment process undoubtedly contributes to the high standards maintained by your journal.

International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. I strongly recommend to consider submitting your work to this high-quality journal. The support and availability of the Editorial staff is outstanding and the review process was both efficient and rigorous.

Thank you very much for publishing my Research Article titled “Comparing Treatment Outcome Of Allergic Rhinitis Patients After Using Fluticasone Nasal Spray And Nasal Douching" in the Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology. As Medical Professionals we are immensely benefited from study of various informative Articles and Papers published in this high quality Journal. I look forward to enriching my knowledge by regular study of the Journal and contribute my future work in the field of ENT through the Journal for use by the medical fraternity. The support from the Editorial office was excellent and very prompt. I also welcome the comments received from the readers of my Research Article.

Dear Erica Kelsey, Editorial Coordinator of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics Our team is very satisfied with the processing of our paper by your journal. That was fast, efficient, rigorous, but without unnecessary complications. We appreciated the very short time between the submission of the paper and its publication on line on your site.

I am very glad to say that the peer review process is very successful and fast and support from the Editorial Office. Therefore, I would like to continue our scientific relationship for a long time. And I especially thank you for your kindly attention towards my article. Have a good day!

"We recently published an article entitled “Influence of beta-Cyclodextrins upon the Degradation of Carbofuran Derivatives under Alkaline Conditions" in the Journal of “Pesticides and Biofertilizers” to show that the cyclodextrins protect the carbamates increasing their half-life time in the presence of basic conditions This will be very helpful to understand carbofuran behaviour in the analytical, agro-environmental and food areas. We greatly appreciated the interaction with the editor and the editorial team; we were particularly well accompanied during the course of the revision process, since all various steps towards publication were short and without delay".

I would like to express my gratitude towards you process of article review and submission. I found this to be very fair and expedient. Your follow up has been excellent. I have many publications in national and international journal and your process has been one of the best so far. Keep up the great work.

We are grateful for this opportunity to provide a glowing recommendation to the Journal of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. We found that the editorial team were very supportive, helpful, kept us abreast of timelines and over all very professional in nature. The peer review process was rigorous, efficient and constructive that really enhanced our article submission. The experience with this journal remains one of our best ever and we look forward to providing future submissions in the near future.

I am very pleased to serve as EBM of the journal, I hope many years of my experience in stem cells can help the journal from one way or another. As we know, stem cells hold great potential for regenerative medicine, which are mostly used to promote the repair response of diseased, dysfunctional or injured tissue using stem cells or their derivatives. I think Stem Cell Research and Therapeutics International is a great platform to publish and share the understanding towards the biology and translational or clinical application of stem cells.

I would like to give my testimony in the support I have got by the peer review process and to support the editorial office where they were of asset to support young author like me to be encouraged to publish their work in your respected journal and globalize and share knowledge across the globe. I really give my great gratitude to your journal and the peer review including the editorial office.

I am delighted to publish our manuscript entitled "A Perspective on Cocaine Induced Stroke - Its Mechanisms and Management" in the Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. The peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal are excellent. The manuscripts published are of high quality and of excellent scientific value. I recommend this journal very much to colleagues.

Dr.Tania Muñoz, My experience as researcher and author of a review article in The Journal Clinical Cardiology and Interventions has been very enriching and stimulating. The editorial team is excellent, performs its work with absolute responsibility and delivery. They are proactive, dynamic and receptive to all proposals. Supporting at all times the vast universe of authors who choose them as an option for publication. The team of review specialists, members of the editorial board, are brilliant professionals, with remarkable performance in medical research and scientific methodology. Together they form a frontline team that consolidates the JCCI as a magnificent option for the publication and review of high-level medical articles and broad collective interest. I am honored to be able to share my review article and open to receive all your comments.

“The peer review process of JPMHC is quick and effective. Authors are benefited by good and professional reviewers with huge experience in the field of psychology and mental health. The support from the editorial office is very professional. People to contact to are friendly and happy to help and assist any query authors might have. Quality of the Journal is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on mental health that is useful for other professionals in the field”.

Dear editorial department: On behalf of our team, I hereby certify the reliability and superiority of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews in the peer review process, editorial support, and journal quality. Firstly, the peer review process of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is rigorous, fair, transparent, fast, and of high quality. The editorial department invites experts from relevant fields as anonymous reviewers to review all submitted manuscripts. These experts have rich academic backgrounds and experience, and can accurately evaluate the academic quality, originality, and suitability of manuscripts. The editorial department is committed to ensuring the rigor of the peer review process, while also making every effort to ensure a fast review cycle to meet the needs of authors and the academic community. Secondly, the editorial team of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is composed of a group of senior scholars and professionals with rich experience and professional knowledge in related fields. The editorial department is committed to assisting authors in improving their manuscripts, ensuring their academic accuracy, clarity, and completeness. Editors actively collaborate with authors, providing useful suggestions and feedback to promote the improvement and development of the manuscript. We believe that the support of the editorial department is one of the key factors in ensuring the quality of the journal. Finally, the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is renowned for its high- quality articles and strict academic standards. The editorial department is committed to publishing innovative and academically valuable research results to promote the development and progress of related fields. The International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is reasonably priced and ensures excellent service and quality ratio, allowing authors to obtain high-level academic publishing opportunities in an affordable manner. I hereby solemnly declare that the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews has a high level of credibility and superiority in terms of peer review process, editorial support, reasonable fees, and journal quality. Sincerely, Rui Tao.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions I testity the covering of the peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, we deeply appreciate the interest shown in our work and its publication. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you. The peer review process, as well as the support provided by the editorial office, have been exceptional, and the quality of the journal is very high, which was a determining factor in our decision to publish with you.